In over 20 years working in finance, and 10 years training finance teams, I never once had a spreadsheet tell me a lie.

Plenty of people did, but the spreadsheet itself? Never.

Now it’s 2025, I’m hearing more and more stories from finance professionals about tools that make things up – confidently, persuasively, yet too often wrong.

We call these lies AI “hallucinations”.

That’s the polite term for when a tool like ChatGPT or Copilot just invents an answer that sounds right but isn’t. It doesn’t know it’s wrong, because it doesn’t actually know anything. It’s not drawing from a database of verified facts. It’s predicting what words probably come next, based on patterns. Which means sometimes those patterns lead it straight off a cliff.

In most industries, that might lead to a harmless laugh. In finance, it can lead to reputational damage, poor decisions, or some very awkward questions from the board. It will erode the trust others have in you very quickly.

Now, I’m not saying don’t use AI. It’s brilliant for getting started. Drafting commentary, building frameworks, or challenging your thinking.

But over the past year I’ve noticed a growing risk – people are beginning to trust it. And the critical thinking required to leverage it powerfully is often missing.

You can see how it happens. You ask it to write a summary of your quarterly results, and it gives you something that sounds like you spent hours on it. You copy it into PowerPoint, tidy up a few numbers, and move on. Then someone asks a question you can’t answer because you haven’t spent time understanding the level beneath it. Or even worse, the number, the logic, or even the assumption behind the comment doesn’t exist anywhere in your data. The AI just made it up.

And it forgot to tell you.

The most dangerous thing about AI hallucinations isn’t that they happen – it’s that they sound convincing when they do and you don’t have any idea if you just take what it says and run with it.

I’ve seen examples in forecasting. Someone asks the AI to explain variances or build a narrative around trends. It’ll happily tell you that margin pressure came from supply chain costs, even when there’s no such data in your file. It sounds credible because that’s the sort of thing finance people say. The model doesn’t need proof – it just needs a pattern.

Or take management reporting. I’ve heard of teams using AI to clean commentary before sending it up the chain. But if the prompt isn’t precise, it’ll sometimes “help” by improving clarity in ways that aren’t factually true. It might reword “cash outflows increased due to project investment” as “cash outflows increased due to higher capital expenditure.” Sounds cleaner and more financy to AI, but the meaning is fundamentally different.

That’s the subtle danger here. It’s not usually the big, obvious errors that cause trouble. It’s the plausible-sounding details that creep into decks, reports, and conversations without anyone noticing. And the exposure you have by not knowing the next level down when the questions come

It’s worth remembering that finance professionals are trained skeptics. We’re wired to challenge assumptions, validate data, and test controls. But AI, with its smooth and confident tone, isn’t like that.

And because it feels modern and efficient, we let our guard down. We assume a tool that can write Shakespeare can also handle a P&L.

Unfortunately, AI isn’t analytical. It’s linguistic. It doesn’t understand what EBIT means, or why free cash flow matters more than revenue growth. It just knows those words often appear near each other in financial writing and picks up the pattern.

And the danger isn’t that AI will replace finance professionals. The danger is that finance professionals go auto pilot, become lazy and stop doing the things that make them valuable – questioning, interpreting, and sense checking – because an algorithm made something sound right.

There’s also another layer to this. When someone spots an AI mistake, it often undermines credibility even more so than if it was just the person. Others question you and the tools you use which is even worse. Imagine sending a board paper that quotes an incorrect statistic or attributes a variance to the wrong driver. Once trust is dented, it’s hard to get back. And the irony is, the person presenting might have no idea where the error crept in.

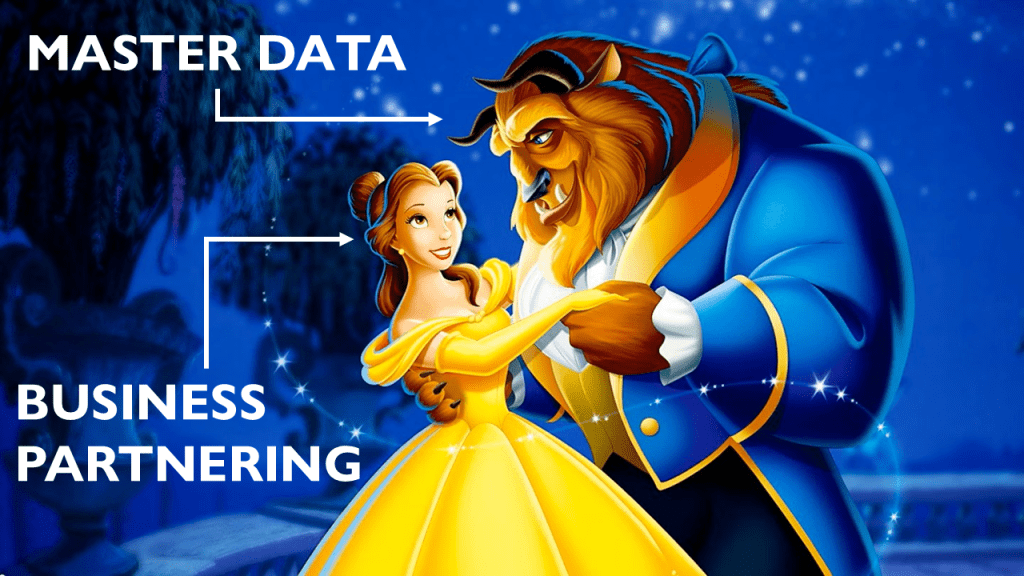

This is why I think the role of finance professionals in the AI era isn’t to become “AI experts.” And be focused on the prompting. It’s to become AI editors and be critical of the answers. The value isn’t in asking the question – it’s in knowing whether the answer makes sense.

So how do you protect yourself?

There are two behaviours that separates responsible use from blind trust…

1 Review anything thoroughly.

When I say thoroughly I do not mean “glancing” at it. Actually checking it as if it was an audit file. Does the commentary line up with the numbers? Are the drivers real? Would you be comfortable explaining this in a meeting if someone asked, “where did that come from?” or “what makes you think that?”

If the answer is anything other than a confident yes, stop and verify.

Just so you know I got AI to write this newsletter article. Then I took what it wrote and carefully edited and reviewed it so I didn’t sound all weird

2 Understand the next level down

AI will pull together everything it has. But commercially it won’t understand the nuance that is there operationally and how all of the numbers connect together

Only you can do that and you often do that through analysis and conversation

That is the next level down. Understanding stuff that isn’t in the data the AI used.

It’s terribly important, nuanced, contextual and will separate you from someone who is just copying and pasting to someone who knows what’s going on and why.

It sounds simple, but it’s not. AI tools are designed to make us feel confident. They fill gaps quickly, they save time, and they write in the language of certainty. And it won’t ask you questions to find out more. It only asks you questions to give you a better answer for what it thinks. You still have to ask it questions.

AI can make you faster, more efficient, and even more insightful – but only if you remain the final layer of judgment.

The moment you remove that, you are at risk of the robots taking your job.

So use AI. Experiment. Get curious. But don’t outsource your professional skepticism. It’s about reducing the hallucinations not increasing them