Most finance professionals I work with aren’t short on effort.

They work long hours.

They care deeply about doing things properly.

They’re loyal to their organisations.

They patiently wait their turn.

Unfortunately many are quietly confused – and frustrated – when the outcomes don’t match the input.

The promotion goes elsewhere.

They have to be detailed but also high level

Get drilled in boardrooms and exec meetings as if you were in charge of every department.

There’s a lingering feeling of: “If I just keep doing good work, good things will come, wont they?”

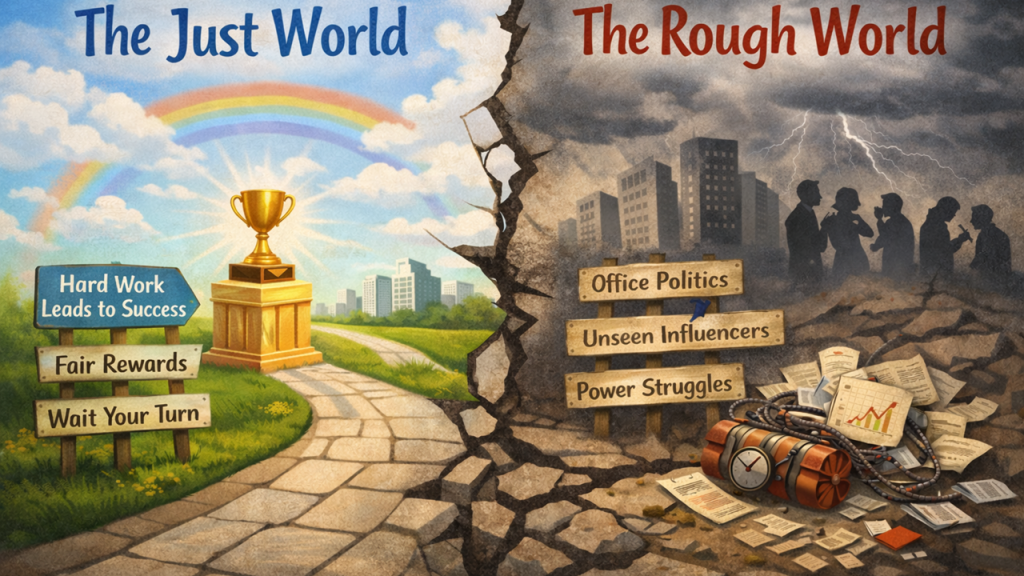

That belief has a name.

It’s called the Just World Hypothesis first described by psychologist Melvin Lerner.

The Just World hypothesis is the belief that the world is fundamentally fair – that good behaviour is rewarded, bad behaviour is punished, and effort eventually leads to outcomes.

It’s a comforting idea. Fairness is a basic human right.

It’s also deeply misleading in organisational life. Especially finance life where it shows up early.

Finance attracts conscientious people. People who value fairness, logic, cause and effect. People who believe that if you meet expectations – or exceed them – the system will notice and rewards will flow bountifully.

Early in a career, this belief is often reinforced. Especially if you grow up in a Big 4 firm

You study hard → you get good grades.

You pass exams → you get letters after your name (and some more cash)

You turn up and do 70 hour weeks → you get promoted from grad to senior, etc.

So it’s not irrational for finance professionals to assume the same pattern will continue inside a commercial organisation.

But somewhere in that transition from doing the work to working with and through others, the rules quietly change.

And no one really explains that to you.

The real world is better described as the Rough World

Organisations are by their nature built with bias and preferences.

They are messy, political, power-laden environments made up of humans with incentives, fears, alliances, blind spots and agendas.

Some more so than others.

Functions by their nature have conflicting agendas. Sales get excited by volumes, finance gets excited by profit.

In a rough world, outcomes don’t always align with effort.

Promotions don’t go to the hardest worker – they often go to the most visible or sponsored.

Influence doesn’t come from being right – it comes from being trusted and understood.

Problems don’t stay neatly in their functional lane – they land wherever someone has credibility and competence. If you’re good at what you do, that’s you

For finance people still operating with a Just World mental model, this feels unfair.

And it is completely unfair.

But we live in the rough world not the just world.

I once worked on a three man team on a business critical project. Which had a major impact on the bottom line of the organisation once we solved it 18 months later.

The team sponsor was duly promoted and lavished with praise.

My reward…..nothing

My effort was maybe informally recognised. But I never received a promotion, pay rise or formal recognition.

It sucked and so I applied a fingers crossed policy

Quietly hoping the system will eventually correct itself.

Which it doesn’t. The only thing that happens is resentment. Sometimes cynicism. Sometimes disengagement. Often it turns into complaining – mainly to other finance people.and your loved ones

What it rarely turns into is a change in circumstance

Because to get that feels like “playing politics”. And politics feels dirty, manipulative, or beneath you.

So what do you do. You double down on competence instead.

And that’s the trap. Unfortunately “doing good work” isn’t enough

In a rough world, technical excellence is table stakes.

It gets you invited into the room.

It does not guarantee you’ll be heard in the room.

I see finance people produce exceptional work that never influences a decision – not because it’s wrong, but because it doesn’t land with the audience that matters.

Or they assume someone senior will notice their contribution without it being framed, positioned, or advocated for.

Or they expect fairness to resolve role ambiguity: “Surely this isn’t finance’s responsibility.”

The organisation doesn’t look after the people who work the hardest.

It looks after the people who provide value, are understood, and are backed. More importantly it looks after the ones who navigate the system most effectively.

Politics isn’t a bad thing – it’s just a thing you need to manage.

Influence, visibility and stakeholder management are not political games.

They are professional skills.

Understanding power dynamics doesn’t make you manipulative – it makes you effective.

Learning how decisions really get made doesn’t mean you’ve “sold out” – it means you’ve stopped being surprised.

In a rough world, waiting your turn isn’t noble – it’s “Just” – and “Just” is rarely rewarded.

Once you see the world as rough rather than just, a few things stop feeling personal.

You start thinking about

👉 Who needs to understand this, not just receive it?

👉 Where does influence actually sit in this organisation?

👉 How visible is my contribution – really?

👉 Who speaks for me when I’m not in the room?

These aren’t cynical questions.

They’re adult ones.

Helping finance professionals thrive isn’t about protecting them from the rough world.

It’s about preparing them for it.

Remember the world of work isn’t fair. It’s a rough world not a just world.

But it is able to be navigated.

Once you stop waiting for fairness and start building influence deliberately, something interesting happens.

The whining stops. Being over looked isn’t a thing. And opportunities come your way.